Mating system evolution

We study how mating systems and sexual asymmetry evolve. Using fungi as model systems, we uncover how mating types, recombination, and gene flow shape adaptation and diversity.

We study how mating systems and sexual asymmetry evolve. Using fungi as model systems, we uncover how mating types, recombination, and gene flow shape adaptation and diversity.

PI

evolution of sexual systems, evolutionary genetics - fungi

Mating types control who can mate with whom, but also regulate the ploidy transition associated with mating, usually through just a few genes at a single locus. Even though mating types restrict compatibility, they are found across the tree of life. If losing mating type function increases mating opportunities, why do so many species maintain them? Why do some, evolve systems such as mating-type switching that preserve the logic of mating types while expanding compatibility? We combine natural variation with experimental evolution to test when separate mating types are favored and when self-compatibility is more advantageous.

Sexual reproduction evolved only once, yet the ways in which haploid genomes fuse, interact and separate again are astonishingly diverse. Across fungi, algae, plants and animals, the cells that mate are almost never identical - whether as dramatically different as sperm and eggs or as subtly distinct as the mating types of fungi and algae. Why is this asymmetry so widespread, and what maintains it?

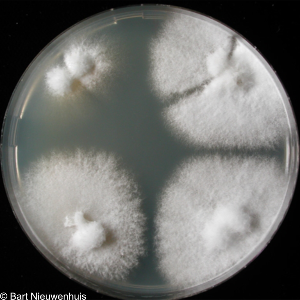

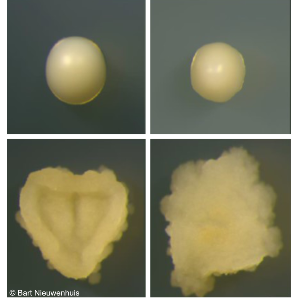

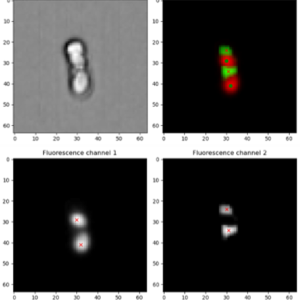

Our group studies how and why these differences evolve and persist. Mainly using the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe as a model, we test hypotheses about the evolution of mating systems, the role of pheromones, and the strength and consequences of sexual asymmetry. Despite being a classic laboratory organism, its natural biology remains surprisingly unexplored. Additionally, we study natural variation in mating types in the mushroom fungus Schizophyllum commune.

Increased compatibility can also occur by increasing additional mating types that in turn increase the pool of potential partners while still preventing selfing. Theory predicts this should be common, yet in nature it is surprisingly rare. Using natural basidiomycete diversity – especially in S. commune – and engineered variants in fission yeast, we study how ecological factors, e.g. density, environmental stability and spatial structure, shape whether more or fewer mating types evolve.

Sex increases adaptive response by separating linked alleles from each other. Mating between individuals from different populations, can further speed adaptation by increasing genetic variation, but it can also introduce maladaptive genes. When populations face divergent selection -whether due to different environments or contrasting selective pressures within a species—sex may repeatedly mix alleles that are beneficial in one context but deleterious in another. This tension shapes how quickly populations adapt and whether they remain genetically cohesive or begin to diverge.

In collaboration with Jochen Wolf, we use experimental evolution, phenotypic assays and evolve-and-resequencing approaches to investigate how sexual reproduction and gene flow influence adaptation to novel and heterogeneous environments.

Both between populations adapting to different environments or between groups within a species such as the sexes – divergent selection generates combinations of alleles that work well together. Recombination can break up these combinations, generating a “recombination load.” To avoid this break up, suppression of recombination can arise around genes that are under divergent selection. This has repeatedly evolved: in mating-type loci, on sex chromosomes, and in regions associated with sex-specific or role-specific adaptations. Understanding how and why recombination suppression evolves helps reveal how genomes partition conflict, maintain coadapted gene complexes, and diversify into new forms. To study the evolution of recombination rates, we use S. pombe in experimental setups to assess how evolvable recombination is, what the effect of structural variation is on recombination and what mechanisms affect recombination rates.